I have this one linguist friend whom I met on a trip to China. He throws rocks at me whenever I get perscriptivist, and I throw rocks at him whenever he says something like “‘brilliant English professor’ is an oxymoron.” We were having lunch for the first time after I got back from France, and I had a couple polyglot confessions to make.

Over the last two months, while I was in France, the language experience I had was almost the opposite of my experience with Mandarin. For instance, in Chinese I can hold conversations, but given a block of intermediate text I kind of blank out. It was totally opposite while I was in France; standing at bus stops and looking at menus, reading French was almost “stupid easy,” given the at least 1,700 cognates with English. Words ending in -ive (addictive) just transform into -if words (addictif); words ending in “-ible” are spelled the same even though the endings are pronounced differently. (“-eeblah” instead of the English “-ibbl,”)

Of course, the “tion” trick comes in handy with other Latin-based languages as well. In Portuguese, “-tion” and the less common “-tions” become “-ção/-ções.” (informação/informações In Russian, the final suffix becomes “-tsiya.” (as in революция/revolyutsiya/revolution.)

Then there’s the whole silent-letter bit. In French nearly ever final consonant is silent. Once you get this down, pronouncing words is less difficult than it seems. Then there are les liaisons, where basically if you have a silent final consonant but the next word begins with a vowel, you actually do pronounce that hidden sound, running it into the next word. Deux, usually pronounced “doo,” when put in front of heures, becomes “doozoreh.”

All of these little tricks, of course, are in theory. Because in reality, French has some difficult sounds. Particular difficulties I had lay in the gutteral rhotic blended with other letters. I could say trop all day long, but ask me facetiously what I had that morning at the boulangerie, and I’ll mumble croissant with toil and embarrassment.

When I tried to actually converse in French, the inside of my head sounded something like this.

Me: I want to say that I plan on traveling. What’s the word for travel?

Brain: You should say 旅行 (lüxing).

Me: No, that’s Chinese. I’m actually not remembering any French at all right now and the person is waiting for me to finish this sentence.

Brain: Ok, how about this; я хочу…

Me: Brain stop that’s Russian, do you want me to fail?

Brain: Yes, I do, because I’m confused right now. What country are we in, again?

Me: 我們在法國… DANG IT BRAIN

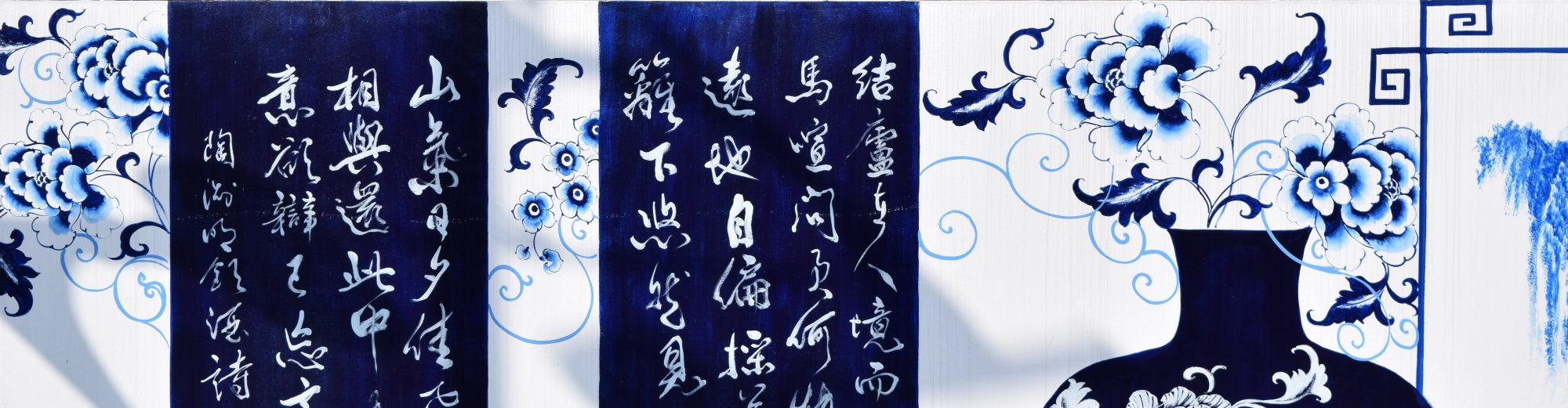

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoyed French, I enjoyed speaking it when I could, reading it, eating it…But on my way home I kept thinking about just how much I love Chinese. How much I was looking forward to getting back into it. Doing characters again. Trying to put sentences into an even number of syllables. Using those strong Beijing Hua sounds. French may someday become language number six, but right now I should really invest my energies into what I’m really good at.

Honestly, after two months in France, I should have been at least beginner fluent. But I wasn’t. I could’ve enrolled in a month-long French course as soon as my TEFL course ended. But I didn’t. I could’ve made arrangements with my host family to speak nothing but French for a half-hour every day. But I didn’t. I could have done so many things that I didn’t end up doing. And it’s not because I was too busy. It’s because I was lazy. The lesson: If you want to do something, you won’t be talking about how you will do it, because you’ll already be doing it.

So, as I lunched with my linguist friend, pouring real maple syrup on my pancakes, I made a hard confession months in the making. “I’ll probably never learn Russian.”

And this is what I love about our conversations; instead of giving me a pep talk or talking about how I should just keep on trying or I should just enroll in a college course or maybe I should buy the Rosetta Stone, or some other encouragement like that that someone would give who’s never learned another language, he forked through his eggs Florentine, frowned, and said, “yeah. It’s not really a fun language for learning.”

You have to cut your guilt expenses. Spending nine years feeling guilty, kicking myself that I wasn’t learning a language that wasn’t really fun to learn, didn’t help me at all. It just gave me something to be ashamed about. At a certain point, continually telling people that I was going to do something that I never truly wanted to do just made me look dumb. And I didn’t even realize until recently that, deep down, I didn’t actually want to learn it. You know how I can tell? Because if I actually wanted to learn it, nothing would get in my way and I would be native-proficient by now.

We must be sincere; we must be honest; we must squint into our souls and find out what we really want. And sometimes it’s better to say nothing about your ambitions, keep them to yourself, then someday surprise people by, say, yodeling perfectly. And they’ll say, “I didn’t know you were learning how to yodel.” But the point is, there’s no point in telling people what you’re going to do because, theoretically, the notional future doesn’t exist, and if you’re not learning it, you’re not learning it.